In the shuffle of moving households recently, I rediscovered my stash of classic mystery novels, and finding myself equipped with a back porch and clement spring weather, decided to take advantage of having forgotten “whodunit” to re-read a few on weekend afternoons.

My favorite author in the genre is Rex Stout, who after a remarkably varied career trying his hand at various jobs while writing on the side, settled down in his forties to start writing crime fiction. In 1934 he introduced the world to his best-known creation: Nero Wolfe, in the novel Fer-de-Lance. He then began cranking out the adventures of Nero Wolfe at a pace of around 1 book each year, and lived to the ripe old age of 88, with Nero Wolfe’s final adventure published a month before Stout’s death in 1975.

The main attraction in Rex Stout’s novels is a detective most people would hate if they met him in real life. When encountering Nero Wolfe for the first time, readers usually notice the same things his interlocutors in the stories do: that he is an overweight, lazy, arrogant, agoraphobic misanthrope who regards his work as a detective as a means to finance his true passions: gourmet food, orchids, and reading.

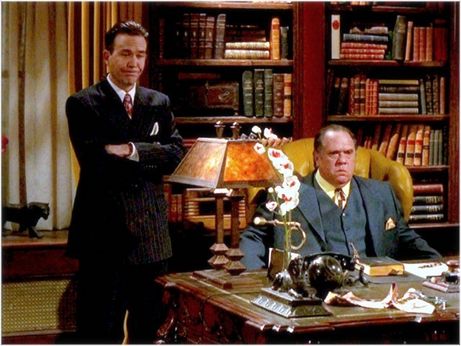

Wolfe’s entire life revolves around his carefully crafted daily routine in his New York City brownstone located somewhere on West 35th Street, a routine regular readers can recite by heart. The hours between 9:00-11:00 am and 4:00-6:00 pm are strictly reserved for Wolfe to spend with his thousands of rare orchids in the plant rooms on the top floor, tended to by himself and his full-time gardener Theodore Horstmann. Lunch and dinner are served at similarly regular times by Wolfe’s gourmet chef, Fritz Brenner. At none of these times is work allowed to intrude, as more than one client has learned to their chagrin.

Wolfe maintains the mid-afternoon and post-prandial periods of his day for dealing with clients, which means almost all the stories involve at least one evening cocktail hour in Wolfe’s palatial office. Unhappily for Wolfe’s rival, Inspector Cramer of the NYPD Homicide Department, while he is almost always present, he is also on duty, and is thus relegated to relieve his stress by gnawing unlit cigars, rather than with a stiff whiskey.

Every Sherlock needs a Watson, especially when the Sherlock in question refuses to leave his house except in the rarest of circumstances. As a result, Wolfe’s assistant (and 1st person narrator of the stories) Archie Goodwin occupies a large role in the series. Some will even argue that it is Archie and not Wolfe who is the real star of the show.

The two are a study in opposites. Archie is the talkative man of action, raised in central Ohio, while Wolfe is silent, hates physical exertion, and is a naturalized US citizen (having been born in Montenegro). Wolfe maintains a limited wardrobe (centered around his favorite color of yellow), while Archie is a dandy. Wolfe, like Sherlock Holmes before him, is notorious for his dislike of women, while Archie is a well-known ladies man who takes a series of dates to the Flamingo (a thinly veiled reference to New York’s legendary Stork Club).

I had the good fortune to first meet Wolfe and Archie in the pages of the 1946 novel The Silent Speaker, arguably one of the best installments of the whole series. It offers all the elements that make up the world Stout created. When the director of a (fictional) government agency is murdered just before giving a speech to a business trade association, Wolfe is hired by the businessmen to solve the case before the trade association is found guilty in the court of public opinion. The two leads are at their peak essences, Wolfe as the imperious genius who won’t be cowed by CEOs, bureaucrats, the NYPD, or the FBI, and Archie as the wiseacre sidekick with a tendency to become a bit too overly invested in a case when a good looking woman is involved.

Like many of the books, the final reveal involves information Wolfe kept concealed from Archie and by extension the reader, because Rex Stout wasn’t out to write classical whodunits where the evidence and method are carefully plotted out for the reader. He was more interested in telling a good story.

And what is the essence of these good stories? More than just mystery novels, they are a psychological study of detectives. What makes Wolfe and Archie tick? I already noted that Wolfe claims to be only interested in his job as a way to finance his true interests, and throughout the stories a recurring theme is that Wolfe frequently takes cases because the bank balance is being drawn down by his massive expenses on rare delicacies of both the edible and floral varieties. But, there is a strong implication that Wolfe is already wealthy, and it would seem that a man with his mind and ability to understand the world could put his resources into investments and live off the proceeds rather than needing to resort to working for his daily bread.

Likewise, why does Archie tolerate Wolfe? A charismatic and intelligent man in his early 30s with a talent for mixing with the rich and powerful could easily find alternatives to being executive assistant and general dogsbody to an obnoxious genius. Most of which would pay better, involve less risk to life and limb, and present as many opportunities for meeting attractive women.

At a glance, it would appear that in their own way, both Wolfe and Archie are showmen and rebels who thrive on demonstrating their talents in the most flamboyant way possible. While they could eliminate the minor inconveniences of life as detectives by going into a different line of work, no other career offers as many opportunities to grab headlines and show up the professionals (the aforementioned Inspector Cramer and his colleagues at the NYPD)

But I would say there’s more to it than that. My read on the duo is that they are playing a little too cool for school when they discuss why they do what they do.

In the first place, Wolfe is a master of misdirection. He habitually conceals information from the police, his clients, and even Archie. He’s even waffled on whether he was born in Montenegro or the United States. In short, Nero Wolfe doesn’t put many cards on the table.

Consider his brief autobiography: “I was born in Montenegro and spent my early boyhood there. At the age of 16, I decided to move around. In 14 years, I became acquainted with most of Europe, a little of Africa, and much of Asia, in a variety of roles and activities. Coming to this country in 1930, not penniless, I bought this house and entered into practice as a private detective.” (from the 1954 short story ‘Fourth of July Picnic’).

The presumption is that Wolfe saw more of the world than any man should during the First World War, and now shelters himself in a life of luxury to make up for the privations and horrors of his formative years. But I think he still carries with those memories a deep need to see justice done. To reveal this deep need would be to reveal a part of his past he wishes to forget, so instead he’s crafted a grand display around his life to give the impression that his crime fighting is a means to finance his life.

More than once Wolfe betrays a personal stake in a case. In The Silent Speaker, for instance, he manipulates the release of information because he feels that delaying the solution to the case will result in an outcome that the victim would have wanted. He’s also been known to take cases pro bono, or fire a client he doesn’t like and go to work on someone else’s behalf.

And Archie? Well, Archie Goodwin (good wins?) has the typical Middle American love of fair play, and assisting Nero Wolfe provides him with a meaning to his life that being a corporate junior executive never could. And as a bonus for a dandy with a distinct blue-collar sensibility, working for the detective to the rich and famous allows him to enjoy both the perks of living high on the hog in mid-century New York, and keeps him grounded and rubbing shoulders with the street toughs.

And it’s that sense of being on the side of right that makes a great detective story. The mystery novel, like the western and the superhero movie, is a tale of good versus evil. It’s a profoundly moral genre, defending the fundamental ideas of right and wrong, even when it’s pointing out the flaws in the established order (something Stout never flinched from doing, such as in The Doorbell Rang, where Wolfe went head to head with J. Edgar Hoover’s corrupt FBI).

And the magic of Nero Wolfe, like the Lone Ranger and Iron Man, is that he’s not just fighting for right, it’s fun to be along for the ride while he’s doing it. Because everyone loves a happy warrior (or a grumpy fat one).

Recent Comments